Hello! This post is now on formerclarity.com. Head over there to keep up with all the latest stuff.

Welcome back to Former Clarity, a newsletter that I’ve been neglecting for the past few months. So, I guess, why have I been neglecting it? Well, quite a few reasons.

For one, as Covid swept the nation (and now re-sweeps the nation) I saw a lot of writers posting faux-inspirational things like, “Okay, let’s crush this quarantine! Wake up and do 12 push-ups and then drink a full smoothie and then hide under your panic blanket and then do 12 more push-ups and…” and I hated all that shit. All the armchair experts who were acting like they had somehow conquered this unprecedented global health crisis felt like the equivalent of seeing someone lying about how great their life was for social media clout. It sucked and was dumb, so I just avoided the whole thing.

And then, well, a lot more stuff happened. I’m not trying to be coy here, but as I watched a lot of people seemingly be awakened for the very first time—because apparently the internet’s memory of tragic events is absurdly short—to the racial injustices and abuses of power by the police, I just didn’t want to take up any space, editorially or otherwise, that could have been better served by listening to people in the communities that were directly effected. Even now, writing a newsletter feels a little unimportant no matter the subject. But, writing is what I like to do, so here I am, another white dude writing on the internet in a newsletter. Oh, what a glorious media landscape indeed.

So, you’re probably asking what brought me back here? Well, again, I had things to say and this feels like the outlet to say them. At the current moment, the thought of pitching any publication feels shitty to me. In part, because I have a job that has kept me aloft through this pandemic, and also because I’d rather see writers who haven’t had that opportunity get it. When I was at The A.V. Club, I tried my damndest to give young writers a chance, and I’d rather leave the road clear for them right now instead of taking up that space then tweeting about how, “Media needs more diverse voices!” But also, no self-respecting publication wants to run this sanctimonious, self-defeating drivel, so here we all are.

I’ve been crying a lot lately. Mostly to music, but sometimes just because. Given my track record, one may assume I’m cranking some Midwestern emo band from the late-aughts and just letting the tears fall, but that’s not been the case. No, no, I’ve been putting on Propagandhi, Crass, Los Crudos, Dillinger Four, and other political bands that I connected with as a kid, and the emotions just come spilling out of me.

As utterly ridiculous as it may seem, I had my so-called “political awakening” earlier than most. I think I was probably 12, and I only wanted to listen to music that had a left-wing sociopolitical message, and I was reading my first books about the the deep, flawed history of the United States. If you doubt that, maybe I’ll have my mom tell you all a story sometime about how I used to debate her friends at the kitchen table about the fact the invasion of Iraq was a tool of American imperialism and nothing more. I sure was fun, huh?

Anyway, I recently was asked to guest on a podcast called Unscripted Moments: A Podcast About Propagandhi, which is hosted by two very smart teachers who also like to discuss the specifics of this modern punk institution. I think the episode will be out in a couple weeks, if you want to hear me go long about the song “When All Your Fears Collide,” which is a pretty great song if you ask me.

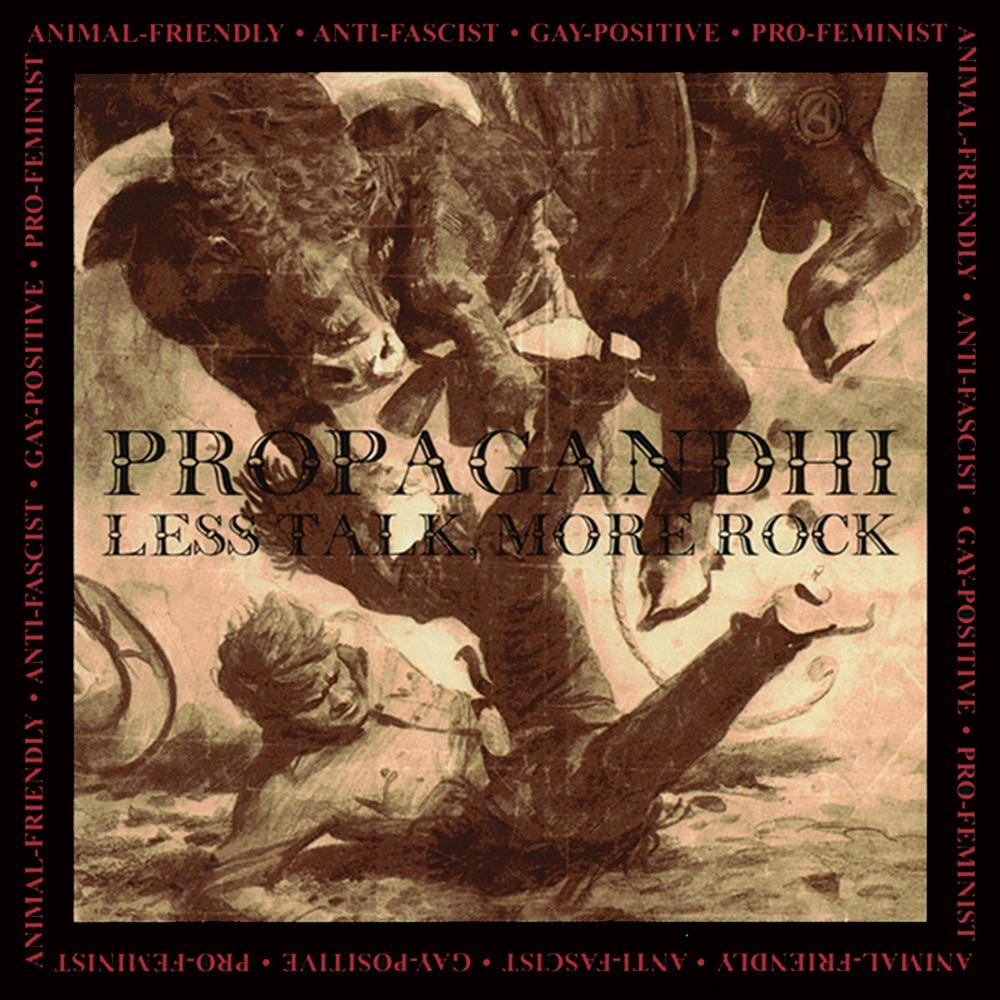

The timing couldn’t have been better, because, as I tweeted a month ago, I had been on a kick with the band. That kick began as I watched the hypocrisy of this Covid situation unfold before my very eyes. A couple weeks prior, I was taking the garbage out to the alley and saw two different parties happening on each side of my apartment building. These were big gatherings of affluent whites, the kind that had—and still have—Black Lives Matter signs hanging in their window. Because they oppose suffering, but only symbolically. I also caught wind of a lot of friends, ones that seemed to only now realize the harsh realities of the United States, posting sanctimoniously all over social media while privately doing the exact opposite of what they championed in the digital realm. I was frustrated, angry, and appalled by the hypocrisy. So, I grabbed my copy of Less Talk, More Rock off the shelf and sat there in my own sanctimonious pod, letting the lessons of yore hit me once more.

Then came Today’s Empires, Tomorrow’s Ashes, an album title that has never wrung more true. The album opener, “Mate Ka Moris Ukun Rasik An,” tells the story of Bella Gahlos, a woman of East Timor who fled her homeland for Canada during the Indonesian occupation (which, go figure, was backed by the U.S. government) and I just broke down. A song I heard for the first time nearly 20 years ago, one that shook me then, made me realize that I’d been complicit in ignoring the importance of these issues by opting, instead, to promote bullshit pop-culture news instead of art that actually fucking said something. The things that radicalized me I had a chance to champion and, more often than not, I got caught up in the cultural milieu that, as per usual, only existed to give upper-class whites more escapism. I’d cared. I thought I was helping. But I was wrong. Anyway, here are some lyrics:

Dickheads shit-talk huddled and single-file. First-world frat-boys and prairie skinheads who will never walk a mile or mourn a murdered friend in this tiny woman’s shoes. Drink up and mumble your abuse. I’m still humbled by it all: around the same time that I was riding with no hands, busting windows and getting busy behind the sportsplex (with Labonte’s older sister decked out in her Speedos), Bella was flinching from the sting of a Depo Proveran “family planning,” her own Pearl Harbor, and a holocaust spanning 25 years to the rest of her life. A prison my country underwrote in paradise. And in the shadows of Santa Cruz, she crossed her fingers behind her back. Built Suharto a Trojan horse and lay still till the motherfucker sent her north where as night fell she emerged with a box under her arm that held her pledge of allegiance and her uniform. She laid it at the gates of the General’s embassy and her whisper echoed into dawn as she disappeared: The truth will set my people free.

The truth will set my people free.

Then I listened to “Bringer Of Greater Things,” a song dedicated to Rodney Naistus, Neil Stonechild, and Lawrence Wegner, three indigenous Canadians who were picked up by the Saskatoon police and driven to an isolated area during a freezing winter and dropped off. They froze to death. This practice was common, and it had a clear purpose: to murder non-white people for having the gall to merely exist. Again, some more lyrics:

Look at our collection of hands, heads and feet to see where we’ve been. Embrace this parody: the ending of things you can believe. We’ll drive you ’til you’re skin and bones and when we finally reach the end, you’ll fall into our open arms, accept our tears of sympathy. Make way for our emptiness. A descent that never ends ’til the one last living thing is the next thing to go. You should know by now that we never come in peace. Endure this tragedy, wrap yourselves in our fantasies. When you think of all you’ve lost, weigh it with what you’ve gained in trade. We’ve given the greatest gift: this savior that will never rise. The Bringer of Greater Things. Creator of Brighter Days. The city cops, a sub-zero night. A midnight ride out of town. The passenger was found frozen to the snow. Our enduring legacy. We bring a better way. Our handshake crushing bone. The blankets that keep you warm, we’ve soiled with disease. The Bringer of Greater Things. Creator of Brighter Days. The hollow songs you’ll sing at the ending of your day.

The first time I ever heard this song, reading the lyrics along with it, I cried (and I do every time I hear it, for the record). By that point in my life, I’d read a good deal about the plight of indigenous communities in America, and I was always acutely aware of the fact that most people were content to brush these things off as having happened a long time ago. But it was happening now, and it was happening everywhere. “We bring a better way. Our handshake crushing bone.” If there has ever been a more astute line about the intersection between imperialism and capitalism, I’ve surely not heard one.

I regret many things in my life, both things I did and things I didn’t do. But one that professionally stings is knowing how I sold out my values—and my genuine tastes—for the sake of assimilation and acceptance. I was told repeatedly that punk and hardcore were juvenile pursuits, that songs about injustice and revolution were “naive,” and that “real music” was something sedate and anodyne, with lyrics that, when placed under even the faintest scrutiny, exposed nothing more than a college degree and a thesaurus to have been the genesis of their creation.

Though it’s comparatively small potatoes in the grand scheme, the amount of banal indie-rock I’ve written about in my life—purely to satiate the masses—is something I genuinely hate. My name is forever attached to work (and music) I am not proud of, because it was vapid escapism and nothing more. I honestly didn’t even care about indie-rock until it was basically a mandate of my job, and since leaving that position three years ago, I’ve drawn a pretty harsh line between what I think is actual, thought-provoking art, and things that exist only to function as a capitalistic white washing of an otherwise powerful art form.

Art should be about something. It should stand for something. It should be able to challenge who you are and how you see the world. Instead, most of it just serves as an additional set of blinders. I hope to never have mine put back on.

If you wish to do some good today, please consider making a contribution (monthly, if you can) to Assata’s Daughters, a Black-led organization that organizes young Black people in Chicago by providing them with political education, leadership development, mentorship, and revolutionary services.